TL;DR

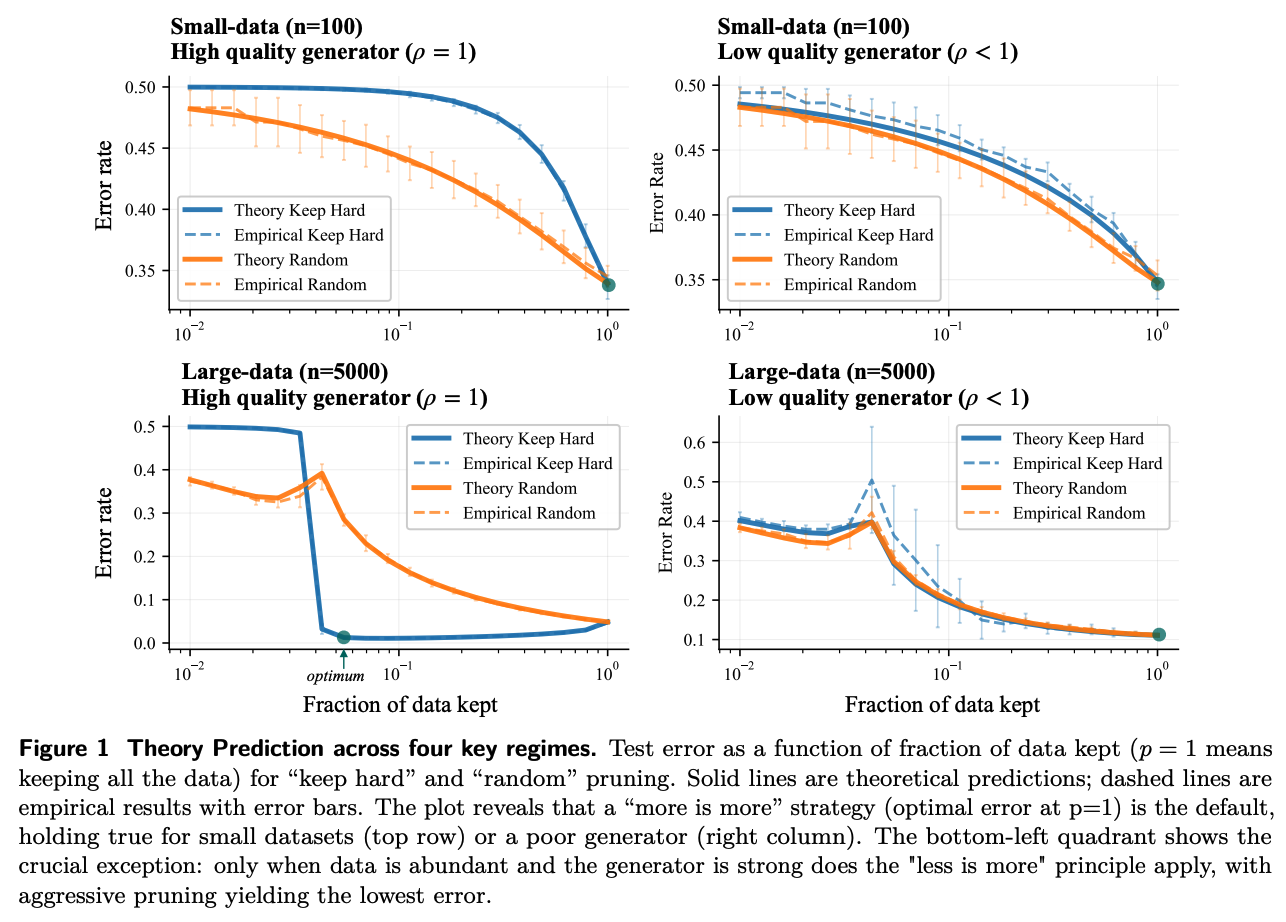

Training LLMs often requiring hundreds of billions of tokens, yet not all data points contribute equally to learning: while some accelerate progress, others are redundant or even detrimental. The paper builds a theory for when a smaller, curated dataset can outperform using all available data in high dimensional learning. It models a label generator, and pruning oracle, then derives test error scaling laws showing that “less is more” only in a specific regime where data is abundant and the label generator is strong, while “more is more” remains optimal in most other regimes.

Methodology

The setting is high dimensional binary classification with a linear teacher and a linear student trained by squared loss, in a proportional asymptotic where dimension and sample size grow together. The weight vectors are defined:

- The ground truth \(w^*\)

- The generator \(w_g\) that produces training labels

- The oracle \(w_o\) that scores example difficulty

The following quantities are defined: Cosine-alignment parameters \(\rho = \langle w_g, w^* \rangle\) and \(\rho^* = \langle w_o, w^* \rangle\) summarizing generator and oracle quality.

More intuitively, a “generator” is the model that produces the labels used for training, which might be imperfect or synthetic rather than the true ground-truth source, for example:

- A smaller or earlier LLM that you query to label reasoning traces, chain-of-thought steps, or preference comparisons, and then use those labels to train a larger student model

- A vision model (say, a strong ResNet or ViT) that assigns class labels or pseudo-labels to images, which are then used as supervision for another model or for data pruning decisions

Then two classes of pruning strategies are analyzed:

- Label agnostic curation: keep an example \((x, y)\) if a binary function \(q(x^\top w_o)\) of its oracle margin equals 1. “keep easy” and “keep hard” corresponding to large-margin and small-margin retention rules respectively.

- Label aware curation: first discard examples whose labels disagree with the oracle’s label prediction, then optionally apply a difficulty-based rule on the oracle margin.

Main Findings

The derived scaling laws show four qualitative regimes indexed by generator quality \(\rho\) and effective data abundance, with sharp transitions in the optimal pruning fraction \(p\).

In three of the four “more is more” is typically correct: test error is minimized at \(p = 1\) when (1) data is scarce (regardless of generator quality) and (ii) when the generator is poor even with abundant data.t

The exception is the abundant data, strong generator regime (\(\rho \approx 1\)), where the optimal error occurs at a small pruning ratio \(p \ll 1\) with a “keep hard” strategy, formalizing a precise sense in which aggressively curated, difficult examples give better generalization than full data.

LLM interpretation

The authors then interpret recent LLM reasoning results:

- For average questions where a base LLM already performs well (strong generator), theory suggests aggressive pruning of hard, high-quality trajectories

- For specially hard subsets where the same model behaves as a weak generator, theory says that retaining more data is beneficial

Limitations

The theoretical model focuses on linear predictors trained with squared loss on Gaussian high dimensional data, so it does not capture nonlinear architectures, cross-entropy training, or realistic LLM optimization dynamics.

The analysis assumes partially aligned oracles and generators: regimes with highly misaligned or adversarial pruners, or tasks with structured inputs beyond the Gaussian setup, are not included in the paper’s formal guarantees